Data is Rectangular and other Limiting Misconceptions

Malloy breaks data's rectangular strangle hold.

In software we express our ideas through tools. In data, those tools think in rectangles. From spreadsheets to the data warehouses, to do any analytical calculation, you must first go through a rectangle. Forcing data through a rectangle shapes the way we solve problems (for example, dimensional fact tables, OLAP Cubes).

But really, most data isn’t rectangular. Most data exists in hierarchies (orders, items, products, users). Most query results are better returned as a hierarchy (category, brand, product). Can we escape the rectangle?

Malloy is a new experimental data programming language that, among other things, breaks the rectangle paradigm and several other long held misconceptions in the way we analyze data.

The Rectangle - Back to Basics

This example is going to start off very simple, but as you will see, we will hit complexity as soon as we need to perform two simultaneous calculations. The problem is that to merge these calculations, we are going to need to take two rectangles and join them.

Orders and Items

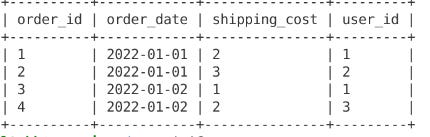

Lets assume two tables: first orders, which looks like the following:

And next, items. Items have an item_id (a unique reference to an item sold), and an order_id (the order in the above table they are part of), the name of the item and the price the item sold for.

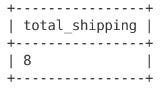

For the purposes of illustration we are interested in measuring two things from this data: our total_shipping costs and our total_revenue from sales. These calculations are pretty easy.

To calculate total shipping with SQL we simply.

select

sum(shipping_cost) as total_shipping

FROM 'orders.csvTo calculate total revenue.

select

sum(price) as total_revenue

from 'items.csv';Dimensionality / Granularity

To build understanding in data, we often look at aggregate calculations at some level of dimensionality (or granularity). In this example we might want to look at each of these calculations by date.

To look at total_shipping by date we can.

select

order_date,

sum(shipping_cost) as total_shipping

FROM 'orders.csv'

GROUP BY 1

ORDER BY 1To look at total_revenue by date, we must join in the items table to the orders table, where the knowledge of the order data is stored.

select

order_date,

sum(price) as total_revenue

from 'orders.csv' as orders

join 'items.csv' as items ON orders.order_id = items.order_id

GROUP BY 1

ORDER BY 1Show me a table that looks like…

Here comes the tricky part. I’d like a table that looks like the one below. It is useful for all kinds of reasons. How does revenue relate to shipping?

You might think you can simply add the shipping calculation to the query above to produce the desired result. Look what happens, the total_shipping calculations are wrong.

select

orders.order_date,

sum(items.price) as total_revenue,

sum(orders.shipping_cost) as total_shipping

from 'orders.csv' as orders

join 'items.csv' as items ON orders.order_id = items.order_id

GROUP BY 1

ORDER BY 1What went wrong?

The problem is that the join interfered with the aggregate calculation. When we joined items to orders, new rows were produced and the shipping cost calculation overstates the shipping. In SQL you quickly learn that you can only perform an aggregate calculation in the correct rectangle. Joining items to orders turns the base calculation of the rectangle into an items rectangle. orders appear more than once in the resulting joined rectangle. The one-to-many join caused a fan-out, duplicating rows from the orders table.

select *

from 'orders.csv' orders

left join 'items.csv' as items

on orders.order_id = items.order_idSolved, join result rectangles

In order to solve this, traditionally, you produce multiple rectangles of the same granularity (in this case, date), and join them. We have our two queries from above — we can run them separately and then join the resulting rectangles.

with orders_date as (

select

order_date,

sum(shipping_cost) as total_shipping

from 'orders.csv'

group by 1

),

items_date as (

select

order_date,

sum(price) as total_revenue

from 'orders.csv' as orders

join 'items.csv' as items ON orders.order_id = items.order_id

group by 1

)

SELECT

orders_date.order_date,

total_revenue,

total_shipping

FROM orders_date

JOIN items_date ON orders_date.order_date = items_date.order_dateWhat just happened?

In traditional data warehousing, the unit of re-usability is a rectangle — some level of dimensionality and aggregate calculations. We produce tables with lots of different levels of granularity and join them. In the computation of each rectangle, we make a pass over the entire data to produce a rectangle. Rectangles are the basis of OLAP Cubes, and the basis of nearly all the ideas in traditional data warehousing.

Adding stuff adds complexity

This gets harder if we want to filter on a date range. The date filter will have to be applied to both queries. Filtering on orders containing a particular item will have to be applied to both underlying queries (though modern databases might optimize for this).

If we want to change the dimension (to say user), we have to duplicate this entire chain of rectangles.

Enter Malloy

Malloy makes the promise that join relations won’t effect aggregate calculations.

In Malloy, data is first described in a network. The network of joined rectangles is a reusable object called a source. Then in a query operation, aggregate calculations are applied. The aggregate calculations can reference any ‘locality’ in the join network and will compute results correctly.

Hopefully, the query below will be somewhat self explanatory.

The query starts by building a source from orders.csv and adding a join to items.csv. The items table will have multiple items per order so we use Malloy’s join_many. The “fanout” relationship in a join is the one piece of data that Malloy needs to perform aggregate computation correctly in any joined table.

The → operator says “apply this query operation to the source”.

The query operation groups by order_date

Perform aggregate calculations for total_revenue and shipping_cost

query: table('duckdb:orders.csv') + {

join_many: items is table('duckdb:items.csv')

on order_id = items.order_id

}

-> {

group_by: order_date

aggregate:

total_revenue is items.price.sum()

total_shipping is shipping_cost.sum()

order_by: 1

}Notice that total_revenue is calculated as items.price.sum(). There are still two source rectangles, orders (the main variables) and items (the nested data). Using a path tells Malloy to calculate the sum in the items sub-table.

The SQL code Malloy writes for this query is non-trivial but actually much more efficient than the multi rectangle queries in that the data is read only once. [See Apendix: SQL Safe Aggregation]

Dimensional Freedom

Once the network has been defined, you are free to produce results from anywhere in the join network. We can change our query to group_by: user_id instead of order_date, for example and get an entirely different result. In SQL we would have had to rewrite underlying queries or persist intermediate results.

query: table('duckdb:orders.csv') + {

join_many: items is table('duckdb:items.csv')

on order_id = items.order_id

}

-> {

group_by: user_id

aggregate:

total_revenue is items.price.sum()

total_shipping is shipping_cost.sum()

order_by: 1

}Source: the basis re-usability in a semantic data model

The join network and calculations can be defined once and used in multiple queries. Reusability is a large topic and we’ll save it for another blog post, but here is basically how it works.

Define a source that contains the join network and common calculations.

source: orders_items is table('duckdb:orders.csv') + {

join_many: items is table('duckdb:items.csv')

on order_id = items.order_id

declare:

total_revenue is items.price.sum()

total_shipping is shipping_cost.sum()

} Use that source in other queries. The order_date query

query: orders_items -> {

group_by: order_date

aggregate: total_revenue, total_shipping

order_by: 1

}and the user_id query

query: orders_items -> {

group_by: user_id

aggregate: total_revenue, total_shipping

order_by: 1

}Non-rectangular Tables

When you think about it, the whole idea that orders and items are two tables isn’t right. If you were building an in-memory data structure, you would have an order node that pointed to an items array. There exists no item without an order.

In an object store, items would just repeated records within orders.

The data exists in two tables, because our tool (SQL) thinks in rectangles so we have to map this into two tables with a foreign key relationship.

A simple illustration of how the data might be nested is to see it in JSON. [see data in JSON in the Appendix]

Nested Repeated

Most modern SQL databases support the notion of nested repeated data within a single table. DuckDB, for example can read and write parquet files which support the notion of nested-repeated data. Notice that items has a sub-schema and is represented as an array of STRUCTs?

Nested data in SQL is very efficient but difficult to use.

Nested data in a database can be treated like a table in a SELECT clause. An UNNEST with a lateral join in a query to iterate over items like the one below. Each of the different databases have (very) different syntax for UNNESTing data. BigQuery is probably simplest and shown below.

SELECT

orders.order_date

SUM(items.price) as "total_revenue"

FROM orders_items as orders

LEFT JOIN UNNEST(items) as items

GROUP BY 1

ORDER BY 1 Unnesting embedded data is still a join and doesn’t solve the rectangle aggregate problem in SQL.

Malloy understands nested tables.

When Malloy reads a schema for a table, it automatically recognizes any nested data and treats it like a join_many . You can simply reference the data as if it were pre-joined using the name of the nested structure (in this case, items). Using the parquet file above, we can re-write our original query. Malloy makes working with nested data much more simple and powerful.

query: table('duckdb:orders_items.parquet')

-> {

group_by: order_date

aggregate:

total_revenue is items.price.sum()

total_shipping is shipping_cost.sum()

order_by: 1

}Nested Data In Results

Malloy also writes nested data. Data is not rectangular. Malloy can easily write hierarchical data as output. Hierarchies can be any depth. Malloy’s language is uniform, so any query operation can be placed in a nest: block. Nested blocks can be as deep as you like. This is a big topic for another day.

query: table('duckdb:orders_items.parquet')

-> {

group_by: order_date

aggregate:

total_revenue is items.price.sum()

total_shipping is shipping_cost.sum()

nest: by_items is {

group_by: items.item

aggregate: total_revenue is items.price.sum()

}

order_by: 1

}From a SQL perspective, there is a lot going on here. We’re unnesting the parquet file, making sure we compute aggregates correctly. We’re also running several queries simultaneously inline to produce the nested result. The SQL for this is non-trivial but very efficient. It still only makes one read pass through the data. [see SQL Nested/Nested below]

Malloy lets you escape the Rectangular nature of most data tools.

The freedom to think about the data in the network in which it already exists without having to constantly translate through rectangles offers new ways to look at problems. The rectangle of a unit of re-usability causes a proliferation of tables and complexity. Malloy’s solution to this problem offers aggregate calculation unbound by dimensions. With Malloy, your data world becomes more simple and comprehensible. We think this is quite a big deal.

Appendix

Safe Aggregation

Malloy Query. Malloy computes aggregates safely regardless of join patterns.

query: table('duckdb:orders.csv') + {

join_many: items is table('duckdb:items.csv')

on order_id = items.order_id

}

-> {

group_by: order_date

aggregate:

total_revenue is items.price.sum()

total_shipping is shipping_cost.sum()

order_by: 1

}SQL Query

SELECT

base."order_date" as "order_date",

COALESCE(SUM(items_0."price"),0) as "total_revenue",

COALESCE((

SELECT sum(a.val) as value

FROM (

SELECT UNNEST(list(distinct {key:base."__distinct_key", val: base."shipping_cost"})) a

)

),0) as "total_shipping"

FROM (SELECT GEN_RANDOM_UUID() as __distinct_key, * FROM orders.csv as x) as base

LEFT JOIN items.csv AS items_0

ON base."order_id"=items_0."order_id"

GROUP BY 1

ORDER BY 1 ASC NULLS LASTExample data in JSON

Data as two tables represented as nested in JSON

order

items

Data as JSON

[

{

"order_id": 1,

"order_date": "2022-01-01",

"shipping_cost": 2,

"user_id": 1,

"items": [

{

"item_id": 1,

"item": "Chocolate",

"price": 2

},

{

"item_id": 2,

"item": "Twizzler",

"price": 1

}

]

},

{

"order_id": 2,

"order_date": "2022-01-01",

"shipping_cost": 3,

"user_id": 2,

"items": [

{

"item_id": 3,

"item": "Chocolate",

"price": 2

},

{

"item_id": 4,

"item": "M and M",

"price": 1

}

]

},

{

"order_id": 3,

"order_date": "2022-01-02",

"shipping_cost": 1,

"user_id": 1,

"items": [

{

"item_id": 5,

"item": "Twizzler",

"price": 1

}

]

},

{

"order_id": 4,

"order_date": "2022-01-02",

"shipping_cost": 2,

"user_id": 3,

"items": [

{

"item_id": 6,

"item": "Fudge",

"price": 3

},

{

"item_id": 7,

"item": "Skittles",

"price": 1

}

]

}

]

SQL Query for Nested/Nested

Malloy Query

query: table('duckdb:orders_items.parquet')

-> {

group_by: order_date

aggregate:

total_revenue is items.price.sum()

total_shipping is shipping_cost.sum()

nest: by_items is {

group_by: items.item

aggregate: total_revenue is items.price.sum()

}

order_by: 1

}SQL Query

WITH __stage0 AS (

SELECT

group_set,

CASE WHEN group_set IN (0,1) THEN

base."order_date"

END as "order_date__0",

CASE WHEN group_set=0 THEN

COALESCE(SUM(base.items[items_0.__row_id]."price"),0)

END as "total_revenue__0",

CASE WHEN group_set=0 THEN

COALESCE((

SELECT sum(a.val) as value

FROM (

SELECT UNNEST(list(distinct {key:base."__distinct_key", val: base."shipping_cost"})) a

)

),0)

END as "total_shipping__0",

CASE WHEN group_set=1 THEN

base.items[items_0.__row_id]."item"

END as "item__1",

CASE WHEN group_set=1 THEN

COALESCE(SUM(base.items[items_0.__row_id]."price"),0)

END as "total_revenue__1"

FROM (SELECT GEN_RANDOM_UUID() as __distinct_key, * FROM orders_items.parquet as x) as base

LEFT JOIN (select UNNEST(generate_series(1,

100000, --

-- (SELECT genres_length FROM movies limit 1),

1)) as __row_id) as items_0 ON items_0.__row_id <= array_length(base."items")

CROSS JOIN (SELECT UNNEST(GENERATE_SERIES(0,1,1)) as group_set ) as group_set

GROUP BY 1,2,5

)

SELECT

"order_date__0" as "order_date",

MAX(CASE WHEN group_set=0 THEN total_revenue__0 END) as "total_revenue",

MAX(CASE WHEN group_set=0 THEN total_shipping__0 END) as "total_shipping",

COALESCE(LIST({

"item": "item__1",

"total_revenue": "total_revenue__1"} ORDER BY "total_revenue__1" desc NULLS LAST) FILTER (WHERE group_set=1),[]) as "by_items"

FROM __stage0

GROUP BY 1

ORDER BY 1 ASC NULLS LAST

This is the same technique that Looker uses for all DBs, not just the ones that don't support CTEs.

Unfortunately, it trades what would be 2 O(N) operations for one O(N^2) operation, which is an unfortunate trade-off.

Additionally, I have found it extremely difficult to debug or tune queries written like this.

Lloyd did a great video presentation of this article at Data Council in March 2023 - I found the accompanying visuals a great addition, link is here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zmmJgwc3oPI